The case against fake police lights

They're certainly annoying, but are they actually effective?

Have you noticed the flashing red and blue lights perched on nearly every major street corner in St. Louis?

If you've driven through the city in the past seven years, they're hard to miss. For those unfamiliar, welcome to a city where simulated police lights have become a standard tool for deterring criminal activity.

I first encountered these lights back in 2017. I remember it clearly: I was exiting I-55 North onto Russell Blvd, headed toward McGurk’s Irish Pub in Soulard. As I approached the intersection of Russell and Gravois, I noticed red and blue lights flashing above the traffic signals, mounted alongside surveillance cameras. My immediate reaction was one of sharp cynicism and disgust. What a lackluster attempt to clean up the streets, I thought.

I still hold this viewpoint today as I pass those same flashing red and blue lights—not just at Gravois & Russell, but on seemingly every major cross-street throughout the St. Louis metro area. The lights, as I’ve observed, are paired with high-resolution cameras:

These surveillance apparatuses—with cameras and flashing lights—have been both mounted on traffic poles at intersections (as seen above) and deployed on trailers parked throughout the city:

Ostensibly, the purpose of the cameras is to enhance public safety through 24/7 surveillance and monitoring. Indeed, according to the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department’s (SLMPD) Real Time Crime Center (RTCC), which was unveiled in May 2015:

“The RTCC is focused on monitoring, deterring, and evaluating criminal activity in real-time by using advanced technology … The SLMPD deploys highly visible cameras that are easily detectable in an effort to deter criminal activity.”

While the concept of 24/7 video surveillance is par for the course in many major cities, the addition of simulated police lights within the surveillance apparatus is not.

Interestingly, aside from the phrases “highly visible” and “easily detectable,” the RTCC website makes no mention (at least none that I could find) of using simulated police lights as part of their criminal activity deterrence strategy. The omission suggests that, in the eyes of those responsible for implementing the lights, their effectiveness was assumed to be self-evident—a foregone conclusion.

The intent behind the simulated lights is presumably to support the SLMPD’s mission of deterring crime by creating the illusion of a stronger police presence, without requiring more officers. Additionally, making these surveillance setups "highly visible" and "easily detectable" may have been seen as a move toward transparency. However, the addition of flashing lights complicates this approach in ways that raise some troubling concerns. Here’s why:

The lights kind of defeat the purpose...

Some might argue that these simulated lights are a cost-effective measure in a city with limited resources. They’re cheaper than hiring more officers and can be installed in high-crime areas quickly. However, their static placement undermines their potential effectiveness.

The problem is that many of these lights haven’t moved in years. Over time, both residents and potential criminals become desensitized to them. Once it’s clear the lights aren’t connected to an actual police presence, their psychological impact fades. In some areas, the number of simulated lights seems to outnumber real officers, further diminishing their deterrent value.

Even if these lights curb criminal activity in certain spots, they likely only displace it rather than prevent it. In fact, by drawing attention to surveillance points, the flashing lights may defeat their own purpose; more discreet cameras could be more effective. While they might offer some short-term value, their static deployment limits their potential to provide lasting safety. Instead of being a dynamic crime prevention tool, these lights risk becoming just another overlooked fixture of the city.

What does the data say?

Despite the widespread presence of these flashing lights, crime rates in St. Louis remain alarmingly high. The city has 40% fewer cops but only 22% fewer residents than it did in 1995, making it likely that more crimes go unsolved or unreported due to the decline in law enforcement personnel.

While city officials cite recent drops in violent crime, there’s some skepticism about the accuracy of the data. Ness Sandoval, a professor of sociology at Saint Louis University, went as far as saying that St. Louis’ crime statistics don’t add up. Others, such as renowned University of Missouri-St. Louis criminologist Rick Rosenfeld, have pointed out that St. Louis may just be part of the overall decline in crime rates being seen across the country. When KSDK interviewed him a year ago, Rosenfeld said:

“Our position relative to some of the other high homicide rate cities may not be improving all that much … You can’t just use the decline to say we’re doing something right when other people are doing different things, or nothing at all, and also showing declines.”

At any rate, recent FBI statistics show that St. Louis continues to rank among the most dangerous cities in the United States. When measured on a “Cost of Crime per Capita” basis, St. Louis ranks third in the country at $11,055 per capita.

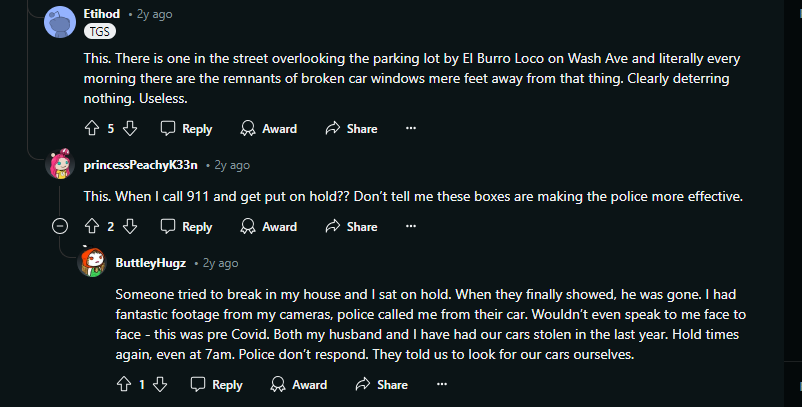

Anecdotally, what I’ve gathered from local friends and Reddit (yes, Reddit, though taken with the prescribed grain of salt) is that the crime persists—even right in front of these surveillance mechanisms. One thread from a 2022 post on r/StLouis echoes this sentiment:

Personally, I’ve witnessed absolute lawlessness firsthand—several times over the summer, and sometimes just a few dozen feet from these flashing lights as I waited at a red light. I’ve also heard from friends who live near these surveillance setups that crime and danger in these areas are not improving—in fact, in some cases, they’re getting worse.

Perhaps I have a limited scope, but from where I sit, the data showing a decline in crime rates doesn’t quite pass the eye test.

The psychological toll is also worth considering…

Beyond the question of effectiveness, the psychological toll of these simulated lights is significant. When cities rely on half-measures instead of deploying real resources, it can create the perception of a weakened social order. The constant presence of these lights doesn’t instill a sense of safety—it feels more like an illusion of security.

This intersects with the broken windows theory, which suggests visible signs of neglect lead to more crime. While these lights are meant to project an image of constant police presence, they may instead imply that the police are everywhere and nowhere at once, potentially worsening the situation.

Consider how visitors perceive these lights. St. Louis already has a reputation for high crime, and the constant sight of flashing lights might make the city feel more like a dystopia than a welcoming place.

While these lights may offer some deterrent effect, they also risk eroding trust in local law enforcement. What’s more concerning is that they reflect the city's reliance on symbolic measures instead of making meaningful improvements to public safety.

In conclusion…

It’s understandable that cities sometimes rely on simple, visible signals like colors and lights to influence behavior—green means go, red means stop. However, applying this kind of approach to complex social issues, where the presence of authority is implied rather than real, risks oversimplifying the problem and treating the public as though they can be easily swayed by mere appearances.

While the use of simulated police lights alongside surveillance cameras may have been intended as a cost-effective deterrent, it runs the risk of being both misleading and ineffective. It assumes that the public—and particularly those inclined toward criminal behavior—can be influenced by a superficial display of authority rather than a real one. This raises important concerns about whether such a tactic is truly a meaningful solution to public safety.

The actual impact of these lights on crime rates in St. Louis remains unclear. With fewer officers on the streets, it’s possible that fewer crimes are being reported, but that doesn’t necessarily mean crime is decreasing. Even if there is a decline, I remain unconvinced that these simulated lights are playing a significant role in that trend.

As a resident of St. Louis, I genuinely hope I’m wrong—that these flashing lights are, in fact, making our city safer. I’m open to changing my view if solid evidence emerges, but so far, I haven’t seen it. What’s clear, however, is that St. Louis deserves more than symbolic gestures. The illusion of security these lights create cannot replace the genuine safety that comes from a visible, trustworthy police presence and meaningful community-based solutions.

What we need are real, tangible investments in public safety—not half-measures that undermine public trust and foster a dystopian atmosphere. It’s time to demand more than flashing lights and empty promises. Our communities deserve strategies that truly serve and protect—not just the appearance of authority, but its reality.